How good it is to be fat! How good to be a member of the corpulent class, smelling just baked rolls and fried blood sausages wafting from the open windows on Park Avenue, and not one of the whip thin hoards confined to lower Manhattan with the stench of raw sewage always in the nose.

Except, they aren’t confined down there. Who do you think is doubling all those Park Avenue chins? Each brownstone has an alien busy at its center. Sleeves rolled up on meaty foreign arms, foreign palms pressing into the family dough. You see that house there, the one with the gay yellow curtains fluttering at the kitchen window? Little does that gloriously tubby family know that along with the rich smells of breakfast, that’s typhoid smeared all over the curtains, typhoid glazing those yeasty rolls.

Never fear, the porcine peace will be restored. Into this monied hush chugs and wahoogahs a new twentieth century ambulance automobile. Three police officers clatter behind on horseback in their long blue coats and soufflé-shaped helmets. They pull up to the curb in front of the Park Avenue brownstone with the yellow curtains. Out of the ambulance pops Dr. S. Josephine Baker.

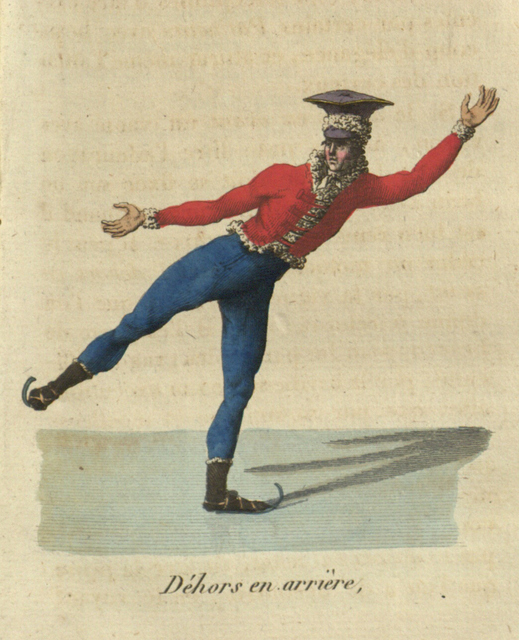

Dr. Jo! A new woman! Fashionably plump, dressed in a man-tailored outfit of her own design, fitted jacket, white stiff-collared shirtwaist dress and tie, jaunty boater with a navy ribbon to top it off. She is the first woman doctor in the new hygiene bureau!

The possibly infected Irish cook in question has already refused to be tested for typhus, but this time Dr. Jo is determined to get a hold of a bit of her urine and blood, come hell or high water. The glass jar and the syringe jostle at the ready in her black leather doctor’s bag. The five, white coated, mustachioed interns, all in black pants creased and cuffed, wait by the ambulance, arms crossed, black boots scuffling and stamping, chatting in low voices amongst themselves. Dr. Jo posts one of the police officers at the front door, one at the back. Then, with the burliest officer by her side, she raps smartly, one-two-three, on the servants’ entrance at the side of the house. They wait, Jo tapping her own black-booted foot impatiently. It annoys her that the police officer, who is stippled with small pox scars on his forehead and cheeks, hums cheerfully under his breath, as if this isn’t an errand of grave importance. She goes to knock again.

The door jolts opens with such force it bangs against the side of the house. Dr. Jo jumps back a step. The cook leaps out on the landing, her cheeks aflame, brandishing a long cooking fork. Dr. Jo glances to the officer for help, but he’s lost his chin in his effort to lean away. “Don’t be foolish,” Dr. Jo says to the cook. “We only want—“

The cook stabs at Dr. Jo with the fork.

Dr. Jo and the policeman rear backwards, then topple together in a heavy tangle on the stone walkway below. The cook slams the door shut.

“Sorry, Doc.” The police officer removes his leg from her chest. “But, say, ain’t that a woman!”

Dr. Jo refuses his offer of help, wrestles herself to her feet. She can feel her own face boiling now. “Onward!” she shouts. They rush in after the cook. Breakfast is still on the stove—white fish in furious boil, stewed apricots and cereal and sausages starting to burn. The police officer stops to remove the pots. “That’s all potential poison,” Dr. Jo says. “Knuckle down, now.”

The lady of the house and her two daughters weep in the parlor. One of the girls is already complaining of a headache from hunger. “What shall we eat?” the girl whimpers. The other servants make their faces as featureless as rising dough, claim to have no idea where the cook is. No use to explain germ theory to them here and now. All they can see is the heavy, dark hair piled high on the back of cook’s head, her well-fed form, her food rich with butter and lard. They cannot imagine what stews inside Mary Mallon.

“Let’s get methodical,” Dr. Jo says. They start at the top of the house, the tidy, nearly empty fourth floor attic where Mary sleeps, and move room by room, floor by floor. But it seems she has disappeared.

Back at the kitchen, the police officer says, “Well, that’s that then,” and looks longingly at the food cooling in the kitchen.

Dr. Jo heaves up the pots and upends them one by one into the garbage bin that sits in the back hallway of the kitchen. She says, “This is a matter of life and death. What are we over-looking?”

And just then, at the end of that hallway, behind several piled up ash cans, Dr. Jo spies a small wedge of blue calico wagging from a closet door. Dr. Jo and the officer drag away the ash cans, evidence of class solidarity, and turn the black doorknob.

Micah Perks is the author of a novel, We Are Gathered Here, and a memoir, Pagan Time. Her short stories and essays have appeared in Epoch, Zyzzyva, Tin House, The Toast and The Rumpus, amongst many journals and anthologies. Her short memoir, Alone In The Woods: Cheryl Strayed, My Daughter and Me, came out from Shebooks in 2013. She has won an NEA, four Pushcart Prize nominations, and the New Guard Machigonne 2014 Fiction Prize. She lives with her family in Santa Cruz and co-directs the creative writing program at UCSC. More info and work at micahperks.com