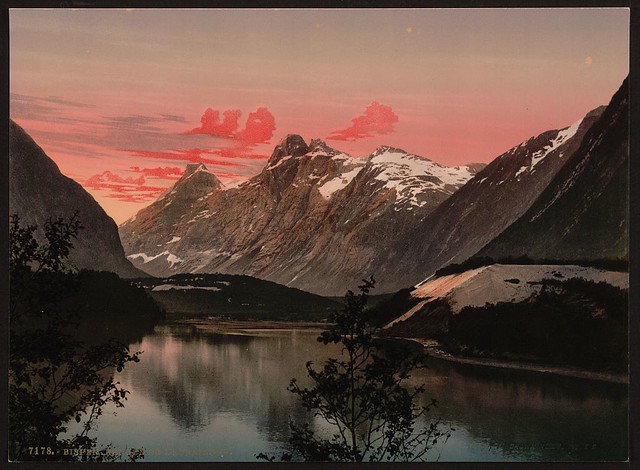

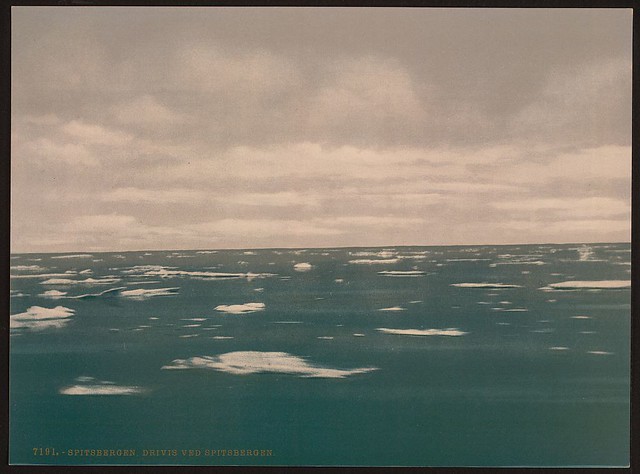

From “Landscape and Marine Views of Norway” (ca.1890-1900), courtesy of The Public Domain Review.

No Tokens Journal is a female-run bi-annual literary magazine based in New York. We are happy to share Pushcart nominee Anne-E. Wood’s story, “Celia, 1978,” which originally appeared in Issue 1.

Too many families live in this town. Look out our kitchen window—plastic sleds left on the sidewalks, a child’s mitten blowing down the drive. Every passing car is a station wagon. I can’t buy milk at the ShopRite without the wheels of a stroller crushing my toes. The schools are full, the skating rink’s crowded with puffy moms, the diners are packed with morbid teenagers who drink coffee and smoke cloves and complain about the crusty rock’n’roll on the jukebox. The dads all line up at the bagel shop on Sundays and talk about football. Everyone complains about Carter and the gas prices and the crime in the city and the weather.

It snowed again today. They closed the library and sent me home.

I pick up the chess pieces strewn in the living room and unclog the basement toilet.

I bake a ham.

February. It will be my birthday next month. I will be old, but everyone will tell me no, it’s not true, thirty-three isn’t old, just look at your skin, and the kids will be older soon and you have your whole life ahead of you. I want to be seventeen. Or I want to be ancient already, calm and wise with my Sanka and spider veins and memories of hard times.

The neighbors are having a party and I told them I’d go, but I won’t. I want to see Benjamin as he walks up the driveway. I won’t talk to him much at first. I’ll let Walter berate him about money. At night, when this house is asleep, I’ll take him down to the basement, or we’ll walk out to the woods. I know what he’ll look like— younger than he is, tougher than he is. Will I look like a mother? Will he be surprised at how fat I got? He was just a kid then, kicking down the back stairs in his torn-up jeans, cocky-smiling when he saw me with Walter in the grass. He hated everything I had to teach him— how to hold the pot in your lungs, how to make a woman come, how you should never suddenly pull out from inside her. She’ll feel you not there for years.

Noah falls skating in his house slippers on the driveway ice and cuts his lip. While I’m nursing him in the living room, Dahlia runs away. She’ll be thirteen in two weeks. I’m not worried, no one’s going to murder her in this sleepy town, but she’s grounded and she’s not supposed to leave the house. She knows which buses go to the mall, which ones go to the city, but I know she wouldn’t dare. I know she’s at that creek in the woods, hanging her head, probably smoking. No one’s going to kill her but me.

Our Volvo conks out every time there’s an errand. It only works when there’s nowhere to go. I try for twenty minutes, freezing in the driver’s seat, turning the ignition key again and again, but nothing. I stroke and kiss the steering wheel. Blue, I say. Come on, show mama you love her. I give up after a while, decide to walk, and take a shortcut through the yard of the abandoned house—the grey Victorian where nobody’s lived for years. Kids go there to drink their parents’ liquor. I hear them sometimes, late at night. The windows are hollowed, the roof might collapse any moment. Weeds and dandelions cover the lawn in summer; in winter, the snow reaches the front door.

I find her at dusk at the creek in the woods, where she always goes. She’s making snowballs and throwing them at a tree. I watch her for a moment, my oldest. Her hair would be a lion’s mane if it weren’t such a rat’s nest.

She throws another snowball at her tennis shoes this time. The wind blows, shaking the trees.

You’re not wearing a warm enough coat, I say. That’s not a coat at all. You’re going to get ice in those shoes.

I hand her my scarf, but she won’t take it. She pulls the hood of her black sweatshirt over her head, covering those eyes.

You look like the Grim Reaper, I say.

Maybe I am.

Is it my time?

It depends. Have you been good?

I’ve tried.

Try harder, she says.

She pulls a stone out of her pocket and cleans it with snow. She started her period yesterday. She didn’t tell me about it. I saw a spot of blood on the toilet seat and it wasn’t mine. I didn’t ask her. Instead, we had a fight about her failing math. She’s wearing Walter’s shirt right now. She’ll be a middle-aged woman with tangled hair, one of those crones you see on the street, who carry too many bags.

Do you know how long you’ve been gone?

Five thousand years?

What do you do out here?

I just want to be alone.

Can’t you be alone in your room?

I like the cold, she says. I like the trees.

Let’s go. Uncle Benjamin is coming in tonight and the house is a mess.

Who’s Uncle Benjamin?

Your Uncle Benjamin. Your father talks about him all the time.

Oh, he’s the kid on the dock.

He was. He’s not a kid anymore. That’s an old photograph.

Isn’t he in Vietnam?

The war’s over, sweetie, many years.

So where has he been?

A lot of places.

I want to go a lot of places.

The trees tower over the houses, their branches curve and bend and twist in all directions. The gnarls of the roots are bulbous and perfect for sitting on. They’re red oaks, maples, sycamores, birches, cypresses, pines. They’re bare now, but the snow on the branches turns pink in the sunset. When we first moved here, I thought I’d never miss the city. I just wanted to have children and read to them under trees. I pick up a pinecone and hand it to Dahlia. She sniffs it and chucks it into a ditch.

You should always ask before you leave the house. I should always know where you are.

You never know where I am.

Because you don’t tell me.

I’m just walking. I’m not smoking or anything.

Always tell me where you’re going.

Fine, she says. I’m going to the movies with Tanya tonight. We’re going to be out until very late. We’re going to meet these guys.

Which guys?

These boys I know.

You’re going nowhere tonight.

You’re fucking horrible.

Your vocabulary is stronger than that.

You’re fucking odious.

Better.

You’re fucking abhorrent.

You’re only twelve.

I wish you would go away.

Me too, I say.

What’s for dinner, anyway?

I baked a ham.

I don’t eat pigs.

Then starve.

I wish I had the discipline.

Are you coming home this evening or should I let Noah have

your clothes?

Give them away to charity.

I like that you’re always thinking of others.

She smiles with half her mouth, and I resist the urge to smack her. I hold out my hand instead. To my surprise, she takes it, and we walk through the woods in silence. It’s going to be one of those winters, the kind that never ends. We’ll have a quick thaw in March, then blizzards in April. Dahlia’s hand is cold and red. I bring it to my lips to blow on it, but she shakes herself free with a sigh.

You’ll like your uncle, I say. He likes to read, like you. He likes to think a lot. And he’s shy.

I’m not shy.

Don’t leave the house without telling me. Especially when

you’re grounded.

I’m not a kid.

No, you’re a woman now.

No, I’m Death, she says, pulling the strings of her sweatshirt. The End is Nigh.

Promise you won’t do this again.

She shakes her head.

Cross your heart?

Hope to die, she says.

Do you love me?

She looks at the trees.

Are we friends?

No, she says, running toward the house.

The four of us sit at dinner, moving the potatoes around with our forks. Walter has opened the good wine. I’ve set a plate for Benjamin, just in case.

Eight o’clock, Walter says. And he hasn’t even called.

He probably got caught in the snowstorm. Maybe you should go out and look for him.

I’m not going anywhere, he says.

Eat your peas, Noah, I say. He eats one pea at a time scrunching his face and his nose. The Band-Aid hangs from his lip. I reach over and try to fix it, but he squirms away.

Nope, Walt says, pouring more wine. Not going out in that at all. I’ll stay right where I am.

He’ll be here, I say.

How do you know that?

Noah, elbows off the table.

The ham tastes like the sole of a shoe. I’ll have to make him something else when he gets here. But maybe he’ll like that I still can’t cook. Maybe it will make me seem young. I’m not going to look out the window because I’ve looked seven times in the last fifteen minutes.

What kind of books does Uncle Ben write? Dahlia asks.

He hasn’t written any books, Walt says.

He writes poetry, I say.

He wrote A poem once. It was hideous.

It was about a horse. Don’t you remember? He was only in high school. The horse was beaten by a pack of boys in the middle of the night. The kids broke into the barn and tortured it with hammers.

That sounds horrible, Dahlia says.

Horses are stupid animals. How are a couple of boys going to beat up a giant horse? It doesn’t make any sense. Your uncle Benjamin gave a recital in the gym and he stood up there in his blazer, shuffling around like he couldn’t find his shoes. You couldn’t understand a goddamn thing the kid said. Sounded like he had marbles in his mouth.

The poor horse, Dahlia says.

It was nonsense.

Walter, he was fifteen.

At fifteen, I’d already played Lear.

Good for you.

It was a lousy poem and he couldn’t recite it to save his life. I told him I would give him acting lessons.

Well, I liked it.

But he’d rather smoke pot and go to the beach.

All I remember is that it was beautiful. That’s what’s important, isn’t it?

I’m sure she loved it. It was just the kind of crappy poem your mother would love. Full of moonlight and waltzing and roses.

And a beaten dead horse, Dahlia says.

Noah, drink your milk. He stabs his fork into his ham and waves it around making robot noises.

Eight-fifteen. For the love of love. Walter stands up and looks out the window again. Dahlia reaches over and turns on the radio.

That was a good ham, Walt says, bringing his plate to the sink. Maybe your best ever.

Dahlia sits on the ledge in the hall, her cheek pressed against the Bay window. She looks like him—his coloring, his eyes. Her eyes are the only beautiful part of her. You’re getting old, girl. Twelve going on ancient.

Counting snowflakes?

She looks at me for a second and shakes her head. She stares back out the window.

Want to talk? I ask.

She shrugs.

Well, I’m here, I say.

My son turns the key of a ballerina music box and puts it up to his ear. It belonged to my mother. The paint has chipped off the face of the ballerina, so she only has two black dots for eyes. You can hear the metal wheels grinding as the girl slowly spins. The music is Satie. Night Music. It’s not a ballet at all. I played it when I was a girl. We had an out of tune upright— a present from the only doctors in town. My father kept it on the back porch through winter and the rainy seasons and the Tennessee summer heat. I taught myself. I wore my mother’s Sunday shoes so I could reach the pedals. My sister loved how I played. She was fourteen and she put her head in her hands. You play nice, Cece. Play that one again for me. It makes me feel like I could just fall in love. Don’t you want to fall in love, Cece? Don’t you want to meet your one and true? That was Frankie with her scabby knees and asthma. She never did find anyone, at least not anyone who loved her back.

Mom? Noah says. How many eights go in one hundred?

I don’t know, Noah. Twelve or so?

My head hurts too much for numbers. My brain is devouring itself. Like part of it is festering, needs to be carved out. I would love to scrape it out of its shell with a pumpkin carver. I have to shut one eye to see. They come once a month, these migraines.

My son! my husband roars from the kitchen.

Something crashes. A stack of plates or a tray of silverware.

My son! he cries again, My only child is going to sail across the sea! Only my thoughts can go with him. Now I hear the chains clanking, and there’s something flapping…something flapping and flapping like wet dresses, wet rags, old shirts on a clothes line, wet handkerchiefs, maybe, and I hear, yes, waves splashing on the hull.

Another crash, louder this time.

Mom, Dahlia sighs from the hall. What’s wrong with Dad?

Nothing, I say. He’s just a lunatic.

But what’s wrong with him?

Why don’t you ask him?

Why is he a lunatic?

I don’t know. Probably someone cast a spell on him.

Who? Noah says.

A nasty queen. Sent him a poisonous shirt, I say.

And he put it on?

And it took away his mind.

And he’ll never be the same?

Never again.

And now everyone’s going to laugh at him? Noah says.

They’ll laugh their heads off, I say.

Their heads will fall off, he says.

Yes, I say. It’s going to be a big mess. Blood spilling from necks. Probably I’ll have to clean it up.

When is the play? Dahlia asks, leaning against the doorframe. She has a habit now of leaning.

Two weeks.

Do we have to go?

Oh, You’re going, I say. You are definitely going.

Walter begins again, hammy and low this time.

Wet towels, I hear sobbing.

And up the stairs, slowly rising…

Or maybe the lost girls on the quay.

And down the stairs, fading…

But why do sailors cry so much? Well, he said, because they keep going away, and so they’re always drying their handkerchiefs up on the masts. And why do people cry when they’re sad? I asked. Oh, he said. To wash the eyes so we can see.

Noah picks a story from the stack of books in the corner. It is about the cat who ends up in firehouse. He is not a good cat and he is not a bad cat, but he gets into all kinds of trouble with the family.

We can read on our own, you know, Dahlia says.

Nobody’s making you listen. You can go to your room and contemplate the paint chips or maybe your math homework.

I can’t concentrate on anything in this crazy house, she says.

Have I told you the story about the girl with the very hard life?

If only her eyes made a sound when they rolled.

It’s snowing hard, Noah says.

Is there going to be school, then?

Oh, you’ll go to school no matter what, I say.

Even if school is closed?

If school is closed, I’ll send you into the woods and you won’t come home until you know all the answers.

Answers to what?

To everything, I say.

Can we go sledding?

No. I’ll read you a story and you’ll go to bed.

When’s whatshisface getting here? Dahlia asks.

Soon.

Did he kill anyone in the war?

You can ask him to read to you, Noah. He loves to read. Pick out some more books he can read to you this week.

I check the window again.

And now who has to read the story about the frogs? Who has to read the story about the owl? Who has to read the spaghetti story? Who has to tell him a new story, one I just make up on the spot? The one about the wolf family and the one about the witch. The one where the witch and the wolf meet at her hut in the forest. The witch and the wolf are friends. She has a party and invites the children from across the highway. They wear cone hats and eat cake. They sing songs and pin the tail on the donkey. There are hula-hoops at the party and the prettiest girl can shake her hips for hours. The wolf shows up with a present: the stomach of a boy. He keeps it tucked under his chin until they bring out the cake. The stupid girl screams. She knows it’s not a present, but the bloody gut of a child. The wolf devours the cake and the witch’s friends. She’s happy. She’s a witch. She never cared for children. She goes riding with the wolf. She hops on his back and they wander through the forest.

Wolfie, it is my birthday, the young witch says, sucking the juice from the boy’s gut. Soon I will be old and fat and you won’t be able to carry me.

“But I’ll carry you as long as I can,” he says. “We’ll go where no one will bother us.”

But how will we eat?

We’ll eat berries and squirrels. When there are no more berries and squirrels, we’ll eat each other.

I sit in the bathtub with my feet resting on the faucet and listen to Alby, the neighbor’s kid, shooting baskets in the driveway. He’s out there on the ice, like he always is, too tall, bouncing the ball like he’s mad at the pavement. He’s only ever been polite to me. He always greets me in front of my car when I come home with the groceries. Can I help you with that, Mrs. Warbler? It’s a terrible winter we’re having, isn’t it? Do you want me to shovel the snow? Can I take Noah off your hands for a few hours? How’s Dahlia doing? I watch him doing pull-ups on the swing-set in the morning, push-ups on the porch in the afternoon after school; at night he shoots hoops in the driveway, no matter the weather. Last summer, he suddenly turned into a man. Or almost a man. He has a man’s chest, but he still swings his arms like a boy, smiles like a girl. He wears his hair in a little ponytail, the kind mothers threaten to snip off in the middle of the night. His mother will be dead in six months. To believe anything else would be pretending. We’ve watched Amelia fade through the last couple of seasons. She’s forgotten we were once almost friends, the time we talked in her kitchen and she told me about her life, her zombie husband, her kids she couldn’t control. I was drunk. I told her how to raise a family. “Whatever happens, they need you.” What gave me the right? These days, she doesn’t remember my name. Maybe if she hadn’t gotten sick, I’d be telling her secrets right now; we’d be in the kitchen, smoking cigarettes, sharing a bottle of wine.

What’s going to happen to that kid in the spring?

What do you want? I say.

The door was unlocked, Walter says. He turns on the faucet and starts to brush his teeth.

I meant to lock it.

I’m getting ready for bed. Is there are problem with that?

I’m having my bath, I say.

I see that. Is there a problem?

Nobody said anything about problems.

Are you going to Sam and Hellen’s tonight?

No.

Why not?

I don’t want to go.

I thought they were the only people you liked.

I’ve got to clean up this house.

Benji won’t even show up at all, he says, his mouth foaming with toothpaste. He’s probably turning around right now, wherever he is. He’s in bed, debating on whether to get up to take a leak. Or he’s groping some girl. In some hotel room.

He’s going to show up, Walter.

Why should this time be different?

He missed his ride last time.

Time before that he missed the bus. Time before that, it was the rain. Time before that he got arrested and then the time he got lost. There are only seven streets in this whole town. Then there was the time when he lost his wallet. What did he need with a wallet?

You think he’s crazy for not wanting to come? You think he wants to hang around us?

What’s wrong with us?

We used to go places. Parties and dances and plays and films and… What was the name of that band?

You never liked to go anywhere. Every time we went out, you just wanted to go home.

What was their name? This is going to bother me all night.

You were always too cold, or too hot, or too pregnant, he says. You hated those parties. Nobody got by without a snarky comment from you.

I’m not going to throw my keys in a basket and snort coke off a nightstand. I’m an old woman.

Then I must be dead.

I miss my sister.

He looks at me for a second, and I feel shy. I slip under the bubbles and draw the curtain. I don’t want to show him my body. It’s not just the weight I’ve gained. It’s that I don’t want to see him, so why should he get to see me?

You never visited her, he says.

I thought about it.

You just feel guilty.

I think about her all the time.

It’s the Catholic in you. Everything’s got to be your fault.

I was barely raised Catholic.

People make choices.

I just think about her voice. I hear it sometimes.

She was a country bumpkin and she didn’t have a thought of her own in her head. I’m not saying she wasn’t good, I’m just saying you’re romanticizing.

I’m thinking about her.

That’s because you have nothing to do.

I’ve been cleaning all day.

You never sink your teeth into anything. Do you know what happens to me when I go on stage?

No, I say. I have no idea.

I disappear a little. I don’t have to be myself for three hours.

I’m worried about Dahlia, I say. She missed school on Thursday.

She probably didn’t miss anything.

Walter…

What are they learning that we can’t teach them?

She’s learning how to lie to her parents, how to hang her head.

Have you noticed her posture?

She’s supposed to be blue. It’s the way she drifts off that bothers me.

Where does she go?

She goes out to the woods, sometimes she goes to the park, talks to the older boys. I don’t like it, I say.

Which boys?

I don’t know, Walter, the boys around town.

Not that Singleton kid.

Sometimes that Singleton kid.

There’s something wrong with him.

There’s nothing wrong with him.

He’s a freak.

He’s sixteen.

He always forgets about Amelia. He lights a cigarette and the smoke fills the bathroom. Walter has taken up the habit of putting his palm on his forehead and inhaling when he wants me to take him seriously, when he knows he’s supposed to feel something. I don’t know when he started doing this, if it’s something he’s learned from acting, or if he’s always done it and I only just now started noticing.

Have you seen her lately? he asks.

Not at all.

I feel for the kid, I really do. Still, there’s something off with him besides all that.

Will you do me a favor?

What?

Will you leave me alone?

Honey, he says. Baby. Light of my life. You’re beautiful when I least expect it. Look at me.

He draws the curtain back and I put the washcloth over my face. He leans into the tub to kiss me, and I let him, at first. He holds me close and his shirt gets wet and sudsy.

I’m in a lot of pain right now, I say, pushing him away.

I can help you with that.

He tries to kiss me more, but I turn my head. He stands up and takes off his wet shirt and leaves it on the floor with the last pile of clothes.

He throws his cigarette out in the toilet, flushes, and leaves, reciting his lines as he heads down the hall.

The kitchen looks like Walter tried to clean it: hurricane ravaged, nothing spared in its wake. There are still broken plates on the floor, the counters are sticky, Noah’s milk remains spilled under the kitchen table, someone left a half sucked orange on the shelf where the cups are suppose to be—-but are not— because they’re all over the house in various corners instead: cups resting on the hi-fi, cups at the foot of the toilet in the downstairs bathroom, cups in the soil of the potted plants. There’s something rotting in the refrigerator: a bag of liquefied collard greens. There’s also a container of pink yogurt, some crayons (a habit of Noah’s: he likes it when they’re cold) a handful of loose grapes rolling around, a bowl of spaghetti with red sauce that has splattered all over the refrigerator walls, Worcestershire sauce leaking from the bottle and coagulating in the fruit drawer, a Tab spiked with whiskey, an empty orange juice container, five squished raisins, a Jello-mold pummeled and destroyed by small hands.

I thought you were going to do the dishes!

I’m studying! She cries back from her bedroom.

How about you study how to carry a dish to the sink?

I’ll do it later, she yells.

I clean half a greasy pan with a scouring pad, but the sponge just moves the mess around, so I give up on it and fill it with hot water to let it soak for the night. I’ll let everything soak tonight. I look out the window. It’s snowing sideways now. You can’t even see the road or the oak tree with the tire swing. You can’t even see the mailbox at the edge of the driveway. The cars lined up on the side of the road are mountains of white. Nobody’s going anywhere tonight. All the guests at the party will stay over. They’ll slip away into the guest rooms, the husbands will betray their wives, the wives will betray their husbands, and everyone will go to work in the morning.

What if he’s lost out there in the blizzard? What if he did forget the name of our street? What if there’s been an accident? I imagine a bloody scene, broken glass, car parts, sirens, Ben trying to hold his own guts together. What if this is how it will end: my love on the side of the road and me in sweatpants with greasy hands? It’s almost nine o’clock. My head begins to throb again. I pour a finger of whiskey in a teacup and it burns my throat and chest as I sip.

I should have tried to make a pie for him. That’s all young men really want. I look for some ingredients: pie crust in a box, milk,

pudding mix. I start to make the pie, but then I realize we don’t have any eggs. You can’t make this kind of pie without eggs, so I give up, have another cigarette and put on some more coffee.

While I’m trying to clean out the fridge, I knock over the can of coffee grounds. I try to vacuum the mess, but I always forget about the faulty outlet, and when I plug in the cord, the circuit breaks and the lights in the whole house go out. I stand for a moment in the darkness until they scream in unison, as though this has never happened before.

It’s alright! I yell back. I’ve got it.

Jesus Christ in a hailstorm.

I’ve got it, I’ve got it.

Where’s my flashlight?

I’ve got it, I say.

In the dark, I trip over the vacuum cord and land on my hands and knees. I curse, but nobody comes to my rescue. I make my way to the basement. The circuit breaker’s behind a pile of old dusty plastic Easter baskets, and I stumble a little before I find the switch.

I hear clapping from upstairs.

If I closed my eyes long enough, would they disappear?

I’ll stay down here for a while. This room is full of old things: exercise equipment nobody uses, old records nobody plays, books nobody reads anymore, but I’ve carved out a space in the junk for my paintings: they’re nothing—portraits I’ve been working on over the years, snapshots of this town, people I know and don’t know, strange things I’ve seen in my dreams. I never show them to anyone anymore. I’m not any good, really. I thought I was once, so many people told me so, so many people I trusted, but I know I’m not. I don’t care anymore what anybody thinks. I don’t do it for anyone but me.

I’m working on a painting of Benjamin I started last week. I’m trying to render the old photograph Walter keeps on his mantle. He’s young in it, probably not even twelve. He’s sitting on the dock, turned toward the sea, with his knee tucked under his arm. His eyes are closed. You can tell even in the black and white photo, his freckled shoulders are burned. I can’t get my painting to look anything like him; I can’t get the dock and I can’t get the sky. I’ve started over so many times. What was he thinking then? Did he even know who he was? Was he even a person yet? How old do you have to be before you know who you are?

Mom, Dahlia says to me from the basement stairs, leaning on the banister. Walter is right. The slouching has gotten worse. Did you want to see me?

I can’t now, baby.

What’s the matter? Are you crying?

No, I’m just working is all.

What are you working on?

Just my paintings.

She looks at the one of Ben.

What’s wrong with his arm?

What do you mean?

It’s crooked.

Is it?

I stand back from it, and look again. She’s right, it is. It almost looks broken. It’s an awful painting. I’ll have to throw it out and start again.

Are you giving that to him?

No.

Why not?

It’s crap. You told me so.

I wasn’t trying to be mean.

You don’t have to try.

I’m sorry, she says, not sarcastically, which is always a surprise.

Go to bed.

I can’t sleep.

You don’t have to sleep. Why don’t you read for a while?

Can I take something for the pain?

There’s some aspirin on my bedside table. You should take that. I’ll come up in a minute. Make yourself some tea.

Are you just going to stay down here all night?

You know how to make tea, don’t you?

All those years he only sent letters. Walter read them to me, and they made us laugh. They started out as short character sketches of the stupid kids in his platoon. What a jackass Pearson was, what a moron Warsawski was, Lorenzini was a prick the shape of penguin, Stevenson had a face that looked like it got caught in a meat grinder, Gaines couldn’t find the verb in a sentence if his life depended on it, Fischbein had the personality of a sidewalk. He wrote to us about how he couldn’t wait to come home so he could go to college and be around people with half a brain. People who read a book once in their lives. He was going to be a professor. Teach the classics. Plato. He said he got it. The story of the shadows and the cave. If there’s one thing he understood, he said, it was that. It’s like everybody’s doing all this dreaming. Everybody’s got this story going on, but who are they without it, who are they when the music shuts off, when the movie ends? That was his line. He believed he was the first one to think about this, the way all kids think they’re the pioneers of truth, the arbiters of who is and who is not completely full of shit. I kept my favorite one. I keep it in a shoebox under the bed, with all my sister’s letters. The notebook pages have yellowed, the blue pen handwriting has faded and smudged.

June 18th, 1970

Dear Celia,

I’m an old man already. The days are okay here. It’s the nights that drive me nuts. The waiting and the quiet. This kid next to me keeps kicking in his sleep. What’s he dreaming about? I want to hold his boots down. He’s not supposed to be sleeping. This is what it’s like. They’re in the trees and grass. They’re in the drops of rain, in the eyes of the gnats. But that’s the thing with me, I can go anywhere I want.

It’s not night at all. It’s June in New York City. Not too hot, no bugs, no humidity, and there’s even a light breeze. You and I are lounging on a blanket, sharing a flask. The boys are home and playing ball like we used to, out on the Great Lawn, throwing Frisbees, strumming guitars. Kids are racing sailboats in the ponds. Jugglers and fire-eaters and Italian ice vendors. A jazz band plays on a makeshift stage and all the couples dance. I want to see the whole city covered in moonlight. Get lost down side streets no one’s ever heard of and sit outside in cafes and talk until the sun rises. When we’re tired of the city, we’ll go live abroad. We could open a little hotel, maybe on the West coast of France. We would put mints and chocolate on all the guests’ pillows. I would bring you tea in the morning in the low seasons, and I’d read you the paper. We won’t have to think about America and everything that’s going on.

This kid sleeping next to me has a girl named Susannah and he’s always talking about her and how one day he’s going to come home and be with her, how they’re going to raise kids on the Pecan Ranch in Tularosa where he was born. But this kid, he doesn’t understand anything about life, so how can he know about love? My love isn’t a young love like this kid’s. What does he know about life already? Did he learn it from the pecans? I don’t know if he’s ever even been with her. The way he talks about it, it’s like he’s never done it, never even had the chance. But I know what it is. I don’t mean this in a corny way, but I want to give you the world. Oh, Celia. I think I can be a man for you. I can be the type of man who’s both hard and soft. I’m going to get a PhD. I’d be the only Doctor Warbler the family’s ever known. I want an office with a globe and shelves and shelves of books. The classics. And you would still work at the library. I’d come in to the library, looking for something. You’d take me to the stacks. Or, we could open a school in Africa. I could just imagine you teaching kids how to read and write. You would draw things on the board and the children would love you. Everybody loves you, Celia Black. You’re everybody’s favorite. Maybe this sounds silly, but I want to bring you cool glasses of water. I want to make it snow for you in hot places. Thank you for the book you gave me. I like the beginning. I’m not going to read it too quick because I don’t want it to end. I’m going to read just one page a day. No, one sentence a day, so it will last even longer.

He could have been on the moon or in Paris, the way he wrote about his life. He hardly ever wrote about anything he saw. I’d heard all the war stories from the draftees and volunteers. But Ben never wrote about killing anyone or the Viet Cong, or even what it felt like to hold a gun. He didn’t write about how his body felt in the heat or the strafing, like you hear about in all the stories, like we saw it when we watched the war on TV. The letters got shorter and shorter. Then they got longer, but they had nothing to do with anything. Sometimes they were jokes that nobody understood, then comic book sketches, drawings of fountains, little diagrams of maps of worlds he invented, the rivers and peninsulas.

How could I know I’d be thinking of him now? How could I know I would suddenly dream about him, as though I always had? How could I know that summer when we were young, before our lives had started, on the grass in Central Park one hot afternoon. July 1960- something. I had dropped out of art school that year. I was supposed to be a radical or something. The war was just a news story; no one we knew had been killed yet. I went to all the protests, but what did I know? Just that war was bad and peace was good and I was going to marry an actor, I didn’t care what anybody thought. I used to be that girl: long hair, t-shirts and cigarettes and flowery dresses bag of paints and brushes, a guitar I moved from apartment to apartment. I never really learned to play. What kinds of thoughts went through my brain? I remember bits of conversations. I might have been too happy to think. If a young woman stands alone in a forest, thinking of nothing, if she could be in this forest or that forest or a city or a cave or wherever, if everyone on earth’s forgotten her, does it matter if she starts to think or scream or if she loses her mind? I was just a body working jobs here and there, drifting through apartments, in and out of the arms of unshaven men. I drank too much Scotch. I slept with too many strangers, I was always waking up in someone else’s bed. But they took care of me. They woke me up in time for work, gave me water, held my head if I got sick. I read all the time on subways and buses, on long Sunday afternoons, but I don’t even remember thinking of the characters or what happened to them in novels or what any of it meant. I saw the newsreels and read the paper, but how could I have cared what was happening in the world? I was in it for the pot and wine. Nothing really bothered me—I was always curled up in some corner somewhere, turning the pages. I was happy to be left alone. The world could disappear for all I cared. Let them bomb it to shreds, as long as I had my corner and my books.

And who was he? A shy eleventh grader who had never seen a naked woman. He quivered when he spoke—not a stutter, but a hiccup, so slight you could almost miss it. There was always a line of sweat above his lip; he was always out of breath. I had to teach him everything, and I loved that, how every touch was new. That afternoon, the two of us were stoned and drunk off cheap red wine he’d stolen from his boss at Kowalski’s. We had no plans for the day; there was nowhere to go. Walter was rehearsing some Greek tragedy in a downtown theater, Oedipus or The Oresteia, I forget, something horrendous and dramatic and loud with a chorus wearing masks and too much shouting, and we’d been fighting all week about one thing or another, about another woman or another man, or about money or the apartment or his parents.

Your brother can be a real pill sometimes, you know that? I said. Benjamin smiled and brought his lips close to my ear.

Then why are you marrying him?

I rubbed the slight stubble of his cheek with the back of my palm.

You don’t even need to shave yet.

When I grow one, I’m not going to shave it.

You will if you get drafted.

I’m not going,

You going to Canada?

Mexico.

Don’t.

Why not?

If you leave, they’ll never let you back in.

I breathed on the back of his neck and he let out a sigh. His skin goose pimpled. I loved the laundry smell of his shirt. I loved how young he was. I could make him do anything I wanted.

Walt would kill me, he said.

You don’t think he’d kill me? Maybe that’s what I wanted: for everything to end.

Come closer, I said.

He put his unsteady hand on my thigh. I leaned into his lips, but he pulled away.

You want to hear a poem? he said.

Walt was right. Those poems were terrible, something like you are the sun’s radiance, the wind’s stolen exhale, you are the sleep of the tide…

I lied to him that night and told him how much I loved them. But I really do love them now: the earnest lousiness of his teenage poems. And the kid, he didn’t have a clue where to put his hands. When he went away, that’s all I could think of: this boy who could do nothing but shuffle.

He came home five years ago, but he never visited us. He lived in Philadelphia for a while, then Buffalo, then traveled as far as St. Paul. Walt had to send him money to bail him out of jail. He beat up an EMT after a bar fight, he shoplifted, he kited a check. He once dropped a line from a payphone in the middle of the night, the static and the highway making it impossible to hear him. I’m going to come see you real soon. I just gotta get settled where I am.

But where are you? I asked, and I thought I was dreaming. Ben?

But the line went dead.

My body stays here in the basement, but my head goes somewhere else. I slip out the front door and wander through the sleepy town. My feet don’t touch the snow. There are only lights on in a few houses. I see a woman in a kitchen peeling carrots. I see two kids playing chess in a hallway. I float through the houses and the rooms, watch how other people live. The neighbors have it worse than we do. Alby Singleton keeps liquor under his bed. At night he climbs out his first floor window to the driveway to shoot hoops and drink. He stands beneath the basket in his pajamas and hooded jacket. I watch his breath in the winter air. He rations. He drinks three sips for every five shots he makes. If he makes twenty shots, that’s fifteen sips. Eighty successful shots equal a bottle, and though he never makes that many in one night (the game gets harder as the night wears on) he almost always gets drunk. Then he climbs into bed with his flashlight, turns on the constellation projector, and begins his math homework, which he does not finish. He stares at the numbers as they toss and turn, as they blend in with the ceiling of stars. He finally falls asleep at three, a fitful, drunken sleep. The six-year-old girl is an insomniac. They think she’s mentally ill; she didn’t begin that way. She never closes her eyes. She is slowly driving herself mad with all that time awake.

The father of that house is in love with the maid. He does not have the courage to even lightly touch her. He only listens for her outside the little room where she sleeps three nights a week. He paces the hallways, longing for her. She is nineteen and from Ecuador. She is fluent in English, she just prefers to not say anything. He speaks a bumbling Spanish to her. A salad of tenses and conjugations. He doesn’t even know what time we’re in. Yesterday he walks to the post office. Five years ago he will leave this country. In fifty years, the earth was so hot it melted. Inclement storms raged when we will be very old.

She doesn’t pretend to care. She spends the long nights writing letters to her boyfriend in Quito. He works for the government.

He doesn’t even miss her.

Amelia Singleton becomes healthy at night. She drives the minivan into the city to meet up with a young couple. At night the three of them perform ambient love rites in the city’s dungeons. They are so tame during the day. The couple works hard to make the rent; he defends the criminally insane; she teaches Math at a high school. They do not attend church, but they attend aerobics classes. On the street, you would think: these are the quiet and bespectacled people I’ve always wanted to be. On the weekends, I watch them at the library where I work. They read intensely in the enormous orange chairs. He devours history books. She rests her feet on a stack of medieval plays. I want to live with them. I want them to read to me. Every other Saturday something breaks. The neighbor’s wife comes to meet them across the George Washington Bridge, and they slip off into the city’s interstices. They walk across the bridge, into dark alleys, by the East River, behind unmarked doors.

Tonight I go with them. I watch them from the corner, try to feel what they feel. Sometimes I sit on a metal swing that hangs from the ceiling’s gritty netting and watch the scene unfold below me. Sometimes I am sandwiched between them, their tender piece of meat. Sometimes I go inside her like he does, to feel her heat, her madness. Our legs intertwine. The neighbor’s wife and I huddle together in a private alcove. When there is a moment’s rest, when we are catching our breaths, I ask her questions. Doesn’t he know? I say. Doesn’t he care about you? Why don’t you leave him, is life like this for you, then? You come here on the weekends and leave him to hover in your house? How do you go back to your home then, with the curtains and the fireplace? How do you continue to make pasta for your kids? Doesn’t he know where you go? Doesn’t he ask questions or hate you for it? She is thoroughly uninterested in chatting, or even making the tiniest noise. She only wants to lick my neck. She only wants to reach her hand inside. I want to see her eyes, I want to see what she feels, but I’m blindfolded. I am the boy, he is the girl, she is the master of everyone. She ties him up and treats him like a slave.

That’s the only way I come: when there’s a group of us, when I know someone will always be waiting.

We don’t bother with the rest of it. With the doing of dishes and the laundry. With the dull conversations in the car, the endless driving around town and the grocery list. We do not go to the neighbors’ parties, we do not borrow sugar, we do not attend the meetings held by the PTA, we do not pretend to care about the football team or who will run for mayor. We only live at night when the world is asleep.

They fuck me and throw me to sea.

It’s full of sunken ships and drowning people. But I fall into it, I suck them in. All those organs, all that brine. I feel them rush all over me. Then it’s just Benji. I feel his weight, his breath, the heat of his skin.

Meeting and parting, parting and meeting! Walter shouts from the kitchen. That’s life! I met his mother, she went away. My son was left, now he’s gone.

The furnace hisses and more plates crash.

Whenever I was lost, I heard that voice, like the wind, like… a storm, like a child, like a child.

—

For previews of issues 1 and 2, or to subscribe, visit the No Tokens website.